World Models: Dreamer V3, IRIS, and Beyond

Deep Model-Based Reinforcement Learning Explained in Depth

Ayeen Poostforoushan (ayeen.pf@gmail.com)

Kooshan Fattah (amirfattah5@gmail.com)

Sharif University of Technology

Why the World-Model Idea Matters

Reinforcement learning (RL) gives us a mathematical language for sequential decision-making: an agent interacts with an environment, receives observations and rewards, and gradually improves its policy to maximize long-term return. Yet the remarkable progress of model-free methods such as DQN, PPO, SAC, and Rainbow hides a sobering fact: they are extraordinarily data-hungry.

The original Atari DQN agent, for example, required roughly fifty million frames — the equivalent of more than two hundred hours of gameplay — to approach human skill. Robots trained with PPO may spend months of real time before mastering a basic locomotion skill.

Humans and animals do not learn this way. We mentally simulate: a child learning to stack blocks imagines what will happen if a tower leans too far, a driver predicts how other cars will respond to a lane change, and even simple creatures such as rats exhibit vicarious trial and error when deciding which tunnel to explore. We are constantly building and querying an internal model of the world. This simple observation is the seed of the world-model revolution in RL.

The central hypothesis is straightforward yet profound: if an agent can learn an accurate probabilistic model of its environment

$$ p(s_{t+1}\mid s_t,a_t),\qquad p(o_t\mid s_t),\qquad p(r_t\mid s_t) $$

and perform planning or policy optimization inside that learned model, it can achieve the same or better behavior with a tiny fraction of real-world interaction. Every advance described below — from Sutton’s Dyna-Q to Dreamer V3 and IRIS — builds on this core idea.

Dyna-Q: the Conceptual Starting Point

Long before deep networks or GPUs, Richard Sutton proposed a simple but powerful scheme called Dyna-Q (1990). Its setting was the classical Markov decision process $(S,A,T,R,\gamma)$: states $S$, actions $A$, transition probabilities $T$, reward function $R$, and discount factor $\gamma$. The goal was still to learn an optimal action-value function

$$ Q^*(s,a) = \max_\pi \mathbb{E}!\left[\sum_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t r_t ;\middle|; s_0=s,;a_0=a,;\pi\right]. $$

Dyna-Q’s insight was to learn a simple environment model on the fly and to use it for extra practice between real interactions. Each time the agent experienced a transition $(s,a,r,s’)$, it updated two things: the Q-table entry $Q(s,a)$ and a one-step model $M(s,a)\mapsto(s’,r)$. Between environment steps it repeatedly “dreamed” by sampling state–action pairs from its experience and applying Q-learning updates using the model’s predictions. In pseudo-code:

Dyna-Q Algorithm

- Initialize Q-table and model $M$

- For each real interaction:

- Update Q with Q-learning

- Update model $M$

- For $n$ planning steps: sample $(s,a)$, query $M$, update $Q$ again

This was a revelation: planning and learning could be unified. A small number of real experiences could be amplified into a much larger synthetic data set simply by replaying imagined transitions.

Power and Limits

Dyna-Q was an elegant demonstration of imagination in reinforcement learning, but it lived in a world of lookup tables and discrete states. Its model $M$ was nothing more than a dictionary mapping state–action pairs to outcomes. As soon as environments became continuous, high-dimensional, or partially observable, this representation collapsed. The core idea survived, however, and would reappear decades later dressed in deep networks and variational inference.

Key conceptual inheritance: The modern Dreamer and IRIS agents can be viewed as very large, differentiable, neural versions of Dyna-Q’s tiny model, learning in latent spaces instead of tables and generating billions of imagined transitions per day on modern hardware.

The 2018 Breakthrough: Ha & Schmidhuber’s World Models

Nearly three decades after Dyna-Q, the idea of a learned internal simulator was reborn in a dramatically richer context. In World Models (2018), David Ha and Jürgen Schmidhuber showed how deep generative modeling could turn raw video-game pixels into a predictive latent space where an agent can “dream” entire trajectories.

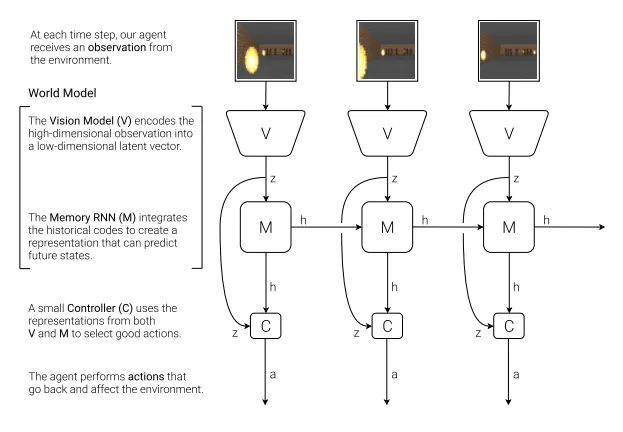

The architecture separated perception, dynamics, and decision making:

-

A Variational Autoencoder (VAE) encodes each high-dimensional frame $x_t$ into a small latent vector $z_t$, trained with the evidence lower bound

$$ \mathcal{L}_{\mathrm{VAE}} = \mathbb{E}_q $$

The prior $p(z)=\mathcal{N}(0,I)$ and the KL penalty encourage the latent space to be smooth and well structured.

-

A Mixture Density RNN (MDN-RNN) predicts a distribution over the next latent state,

$$ p(z_{t+1}\mid z_t,a_t) = \sum_k \pi_k ,\mathcal{N}\big(\mu_k,\sigma_k^2\big), $$

where the LSTM’s hidden state captures temporal context. By mixing Gaussians, it can model the multimodal uncertainty of video-game futures.

-

A simple linear controller maps $[z_t,h_t]$ to an action

$$ a_t = W_c [z_t,h_t] + b_c. $$

Instead of gradients, the controller’s parameters are evolved with Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES), since backpropagating through a stochastic world model is awkward.

These three components were trained in separate phases: first the VAE on collected random rollouts, then the MDN-RNN on latent sequences, and finally the controller entirely inside the learned world. The result was striking: an agent could reach competitive performance in CarRacing and VizDoom tasks without ever seeing new real frames during policy optimization.

Conceptual Lessons

Ha and Schmidhuber proved that accurate latent dynamics are enough for control. But they also exposed the price of modularity: since the three modules were trained separately and the policy never saw raw pixels, the system could not fine-tune representations end-to-end, and evolution strategies remained sample-inefficient. These shortcomings motivated the next leap forward.

The Dreamer Family: Differentiable Imagination

Dreamer (2019–2020) by Danijar Hafner and collaborators answered the call for end-to-end differentiable world models. Instead of discrete training phases, Dreamer jointly trains a compact latent model and an actor-critic policy by performing policy optimization inside the model itself. The core is the Recurrent State-Space Model (RSSM).

The RSSM introduces a deterministic hidden state $h_t$ alongside a stochastic latent state $z_t$:

$$ h_t = f_\theta(h_{t-1},z_{t-1},a_{t-1}),\qquad z_t \sim q_\phi(z_t \mid h_t,x_t). $$

The decoder reconstructs observations and predicts rewards, and a KL-regularized objective.

ensures that the learned latent dynamics match real environment trajectories.

Crucially, Dreamer performs imagined rollouts in latent space: starting from a real latent pair $(h,z)$, it samples actions from the current policy, predicts the next deterministic and stochastic states, and obtains imagined rewards and values entirely without new environment frames. Because the latent transitions are differentiable, gradients flow through these imagined trajectories, allowing the actor and critic to be updated with standard policy-gradient methods.

Dreamer Training Loop

- Collect real episodes with the current policy.

- Update the world model on the replay buffer.

- Starting from latent states, imagine rollouts of horizon $H$.

- Optimize actor and critic on these imagined trajectories.

- Repeat imagination and policy updates many times per real step.

The effect is dramatic: every real step seeds many cheap imagined steps, driving up sample efficiency without sacrificing gradient-based learning.

From Dreamer to Dreamer V2

Dreamer V2 refined the latent representation by replacing Gaussian latents with categorical discrete variables. Using a straight-through Gumbel-Softmax estimator, it preserved differentiability while avoiding the posterior collapse sometimes seen with continuous VAEs. Discrete codes proved more stable and expressive, letting each category specialize in different aspects of the environment.

Dreamer V3: Robust, Domain-General World Models

The third generation, Dreamer V3 (2023), brought the approach to full maturity, achieving human-level or better scores on 55 Atari games and excelling on difficult continuous-control tasks such as quadruped locomotion and pixel-based manipulation. It introduces several key innovations that stabilize training and extend performance across diverse reward scales and domains.

-

Symlog predictions transform values and rewards with $$ \operatorname{symlog}(x)=\operatorname{sign}(x)\ln(|x|+1), $$ linear for small (|x|) and logarithmic for large, taming gradient explosions from rare but high-magnitude rewards.

-

Free-bits regularization ensures every latent dimension carries at least a minimum amount of information by modifying the KL loss to

$$ KL_{\text{free}}[q|p] = \max(\beta \cdot KL[q|p], \text{free bits}). $$

This guards against degenerate latents and posterior collapse.

-

A robust replay buffer carefully balances on-policy freshness with off-policy diversity, allowing the model to learn long-horizon dependencies without catastrophic forgetting.

The result is a system that can seamlessly handle everything from proprioceptive continuous control to rich visual Atari domains, setting new state-of-the-art results while remaining computationally practical.

Takeaway: With Dreamer V3, the vision of Dyna-Q is fully realized: an agent can gather modest real experience, learn a compact predictive model, and improve its policy almost entirely through internally generated trajectories, with gradient signals propagating through every component.

IRIS: Transformers as World Models

The most recent leap in this lineage is IRIS (2023–2025), which replaces recurrent dynamics with a transformer world model. Transformers have revolutionized natural language processing and computer vision by capturing long-range dependencies through self-attention. IRIS shows they are equally powerful for modelling environment dynamics.

The first stage of IRIS is a discrete autoencoder (akin to a VQ-VAE), which converts every input image into a grid of tokens:

$$ E_\phi : \mathbb{R}^{H\times W\times C}\rightarrow {1,\dots,K}^{h\times w}. $$

Each token is an index into a learned codebook $\mathbf{e}\in\mathbb{R}^{K\times d}$. This tokenization is crucial: instead of modeling pixels directly, IRIS predicts the evolution of a discrete sequence of symbols.

The transformer then treats the evolving trajectory $(s_0,a_0,r_0,s_1,\dots)$ as a single long sequence of tokens and predicts its continuation.

Because self-attention sees every past token at once, it can model long-horizon dependencies that RNNs compress into a single vector.

IRIS generates imagined rollouts by autoregressively sampling future tokens, alternating between action, reward, and next-state symbols:

IRIS Imagination Rollout

- Start with current state tokens $\mathbf{z}_t$.

- Append action token $a_t$ sampled from the policy.

- Predict reward and next state tokens using the transformer.

- Feed them back to produce $z _{t+1}$, and repeat for horizon $H$.

Because both the policy $\pi_\theta(a|\mathbf{s})$ and value function $V_\psi(\mathbf{s})$ operate directly on the same discrete token space, the entire system remains end-to-end differentiable and easy to scale. Increasing the transformer’s width, depth, or context length translates directly into better predictive and control performance, just as in large language models.

Because both the policy $\pi_\theta(a|\mathbf{s})$ and value function $V_\psi(\mathbf{s})$ operate directly on the same discrete token space, the entire system remains end-to-end differentiable and easy to scale. Increasing the transformer’s width, depth, or context length translates directly into better predictive and control performance, just as in large language models.

Advantages Over RNN-Based World Models

- Long-range planning: Attention enables explicit connections across hundreds of steps, supporting multi-minute strategies that would strain an RNN’s memory.

- Scalability and transfer: The same architecture can leverage decades of research on transformer training, distributed optimization, and model scaling.

- Sample efficiency: Benchmarks such as Atari-100k report human-normalized scores above 2.0, exceeding Dreamer V3 while using fewer environment interactions.

- Modality agnosticism: Any sensor—images, audio, proprioception—can be tokenized and added to the same sequence.

In short, IRIS demonstrates that the transformer revolution extends far beyond language and vision, making it a natural backbone for world models in robotics, games, and potentially real-world agents.

Architectural Evolution and Deep Comparison

The progression from Dyna-Q through Dreamer to IRIS is not merely chronological but conceptual. Each generation attacks a fundamental bottleneck in sample-efficient decision making.

Below is a concise comparison table summarizing the generations, their representations, temporal models, policy-learning method, and signature innovations.

| Generation | Representation | Temporal Model | Policy Learning | Signature Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dyna-Q (1990) | Tabular states | Lookup table | Q-learning + planning | Unifying model learning and planning |

| World Models (2018) | Continuous VAE latent | MDN-RNN | Evolution Strategies | Latent imagination from pixels |

| Dreamer V1/V2 | Gaussian / categorical latents | RSSM (recurrent state-space) | Actor-Critic with imagined rollouts | End-to-end differentiable world models |

| Dreamer V3 | Categorical + symlog scaling | RSSM with free-bits regularization | Robust actor-critic | Stability and domain generalization |

| IRIS | Discrete tokens | Transformer self-attention | Transformer-based actor-critic | Long-horizon, scalable imagination |

The lesson is clear: richer representations (from tabular to discrete tokens), more expressive temporal models (from lookup tables to transformers), and tighter policy–model integration have yielded exponential gains in sample efficiency and capability.

Beyond Benchmarks: Challenges and Open Problems

Despite spectacular benchmark results, world models face unsolved challenges that keep them at the research frontier.

Model Bias and Distribution Shift

A learned world model is never perfect. Small systematic errors can accumulate during long imagined rollouts, leading to model bias — policies that exploit inaccuracies rather than true dynamics. Distribution shift exacerbates this: as the policy improves, it visits novel states not well-covered in the replay buffer, where the model may be unreliable. Techniques such as conservative value estimation, adaptive horizon selection, or uncertainty-aware planning remain active research areas.

Exploration and Representation Learning

Learning a rich latent space is not automatic. Sparse-reward tasks still pose difficulties because the model may fail to represent rare but crucial states. Intrinsic motivation, curiosity-driven objectives, and contrastive self-supervision are promising but not yet fully solved at scale.

Computation and Energy

While world models reduce environment samples, they often increase compute due to large neural networks and heavy imagination workloads. Training a high-capacity Dreamer or IRIS model can require dozens of GPUs or TPUs. Finding architectures that are both sample- and compute-efficient is essential for deployment on edge robots and embedded systems.

Future Directions

The poster rightly emphasizes that today’s achievements are just the beginning. Several exciting research frontiers are already visible:

-

Multimodal world models: Future agents must integrate vision, audition, proprioception, and natural language. Token-based transformers like IRIS are naturally suited to fuse such diverse streams.

-

Hierarchical planning: Combining world models with goal-setting or option frameworks could enable reasoning over days or weeks of simulated time. A two-level policy

$$ g_t\sim\pi_{\text{high}}(g|s_t),\qquad a_t\sim\pi_{\text{low}}(a|s_t,g_t) $$

is one promising path.

-

Meta-learning and few-shot adaptation: Agents should rapidly adapt their internal model to new environments without long retraining. In-context adaptation and model-agnostic meta-learning are key techniques.

-

Theoretical foundations: We still lack sharp guarantees on how model accuracy translates into policy performance and on the sample complexity of imagined updates.

As these directions mature, world models may become the standard backbone for truly general-purpose intelligent agents.

Concluding Perspective

World models—once a conceptual curiosity—are now central to modern sample-efficient RL. From Sutton’s Dyna-Q to Ha & Schmidhuber’s pixel-based world models, from Dreamer’s differentiable imagination to transformer-based IRIS, the field has evolved rapidly. The path forward will require balancing model fidelity, computational cost, and robust policy learning under distribution shift. If these challenges are addressed, world models will enable agents that learn faster, adapt better, and reason farther into the future than ever before.